The deadly ingredient in Victorian bread

Friday, November 1, 2024

In Victorian-era England, as in most of human history, bread was a dietary staple, and white bread, which was seen as containing fewer impurities and was associated with the upper class, was increasingly in vogue. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| I n Victorian-era England, as in most of human history, bread was a dietary staple, and white bread, which was seen as containing fewer impurities and was associated with the upper class, was increasingly in vogue. Indeed white bread was so desirable that some British bakers resorted to using questionable ingredients to bleach their loaves. One such ingredient was alum, an aluminum-derived chemical compound that is toxic when consumed. It made bread not only whiter, but also heavier, allowing bakers to charge more for their wares and supplement flour doing food shortages. Alum was also cheaper than flour, meaning bakers could pocket more profits — but unfortunately, all this came at the expense of public health. |

|

|

| Alum, when consumed regularly, caused digestive issues and diarrhea, the latter of which could be fatal to young children at the time. In the mid-1850s, prominent English physician John Snow proposed a connection between Brits' poor health — notably the widespread prevalence of rickets, a bone-softening disorder — and the alum-filled bread they were consuming, a theory that came to be viewed in scientifically favorable light in the decades that followed. |

|

| Without widespread awareness of these health issues, however, food adulteration — adding cheap ingredients to keep costs down and production up — persisted throughout much of the 19th century; plaster of paris and chalk were also commonly added to bread. Regulations such as Britain's 1860 Adulteration of Food and Drugs Act sought to curb the use of harmful additives in food, but were not mandatory nor strictly enforced. A revision in 1875 was taken more seriously, and remained in effect for some 60 years until updated government public health guidelines and food safety laws came into place. |

|

|  |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| Percentage of the Earth's crust made up by aluminum | | | 8.23% |

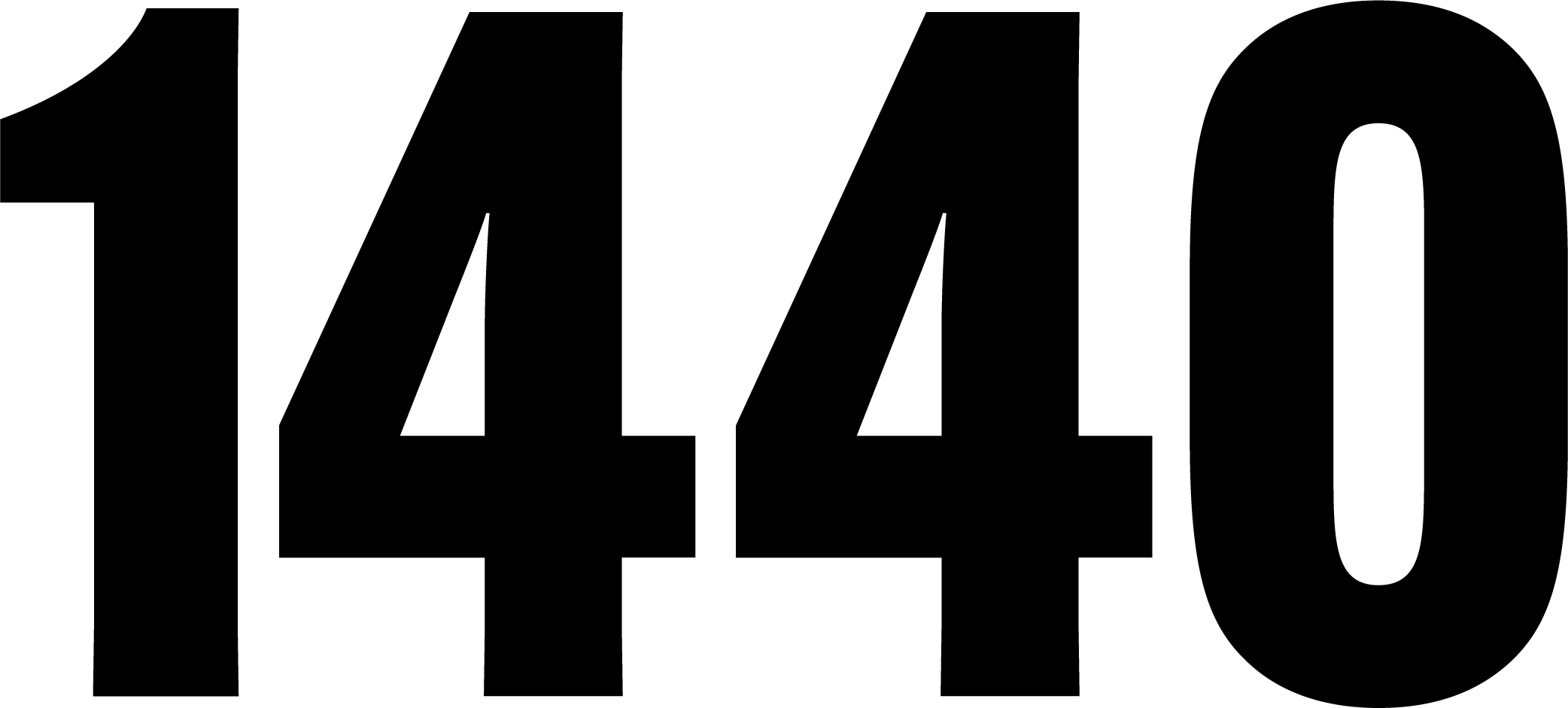

| | | Average life expectancy (in years)in 1850s England | | | 40 |

| | | Average life expectancy (in years)in 1850s England | | | 40 |

|

|

|

| Bread slices thrown away daily in the U.K. in 2022 | | | ~20 million |

| | | Ingredients in a traditional loaf of bread (flour, salt, yeast, water) | | | 4 |

| | | Ingredients in a traditional loaf of bread (flour, salt, yeast, water) | | | 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

| | Did you know? |

|

|

Victorians' favorite shade of green was poisonous. |

|

| Scheele's green, named for the chemist who originally invented it in 1775, was a bright, rich color similar to emerald that was hugely popular in 19th-century England. It also happened to contain arsenic. Despite its toxicity being known by the inventor and some experts, the pigment was used in the production of clothing, wallpaper, and even children's toys. Contact with arsenic-laced clothing or other household items often resulted in rashes or sores; some people suffered fatal respiratory issues. Factory workers who produced goods with the pigment had it even worse: Matilda Scheurer, a 19-year-old worker who made artificial flowers, died from the exposure, but not before the whites of her eyes turned green. Regulations around tracking and disclosing arsenic use went into effect in the U.K. in 1851, and by the end of the 19th century, manufacturers of various goods had all but replaced the toxin with safer ingredients. |

|

posted by June Lesley at 7:04 AM

![]()

![]()

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home