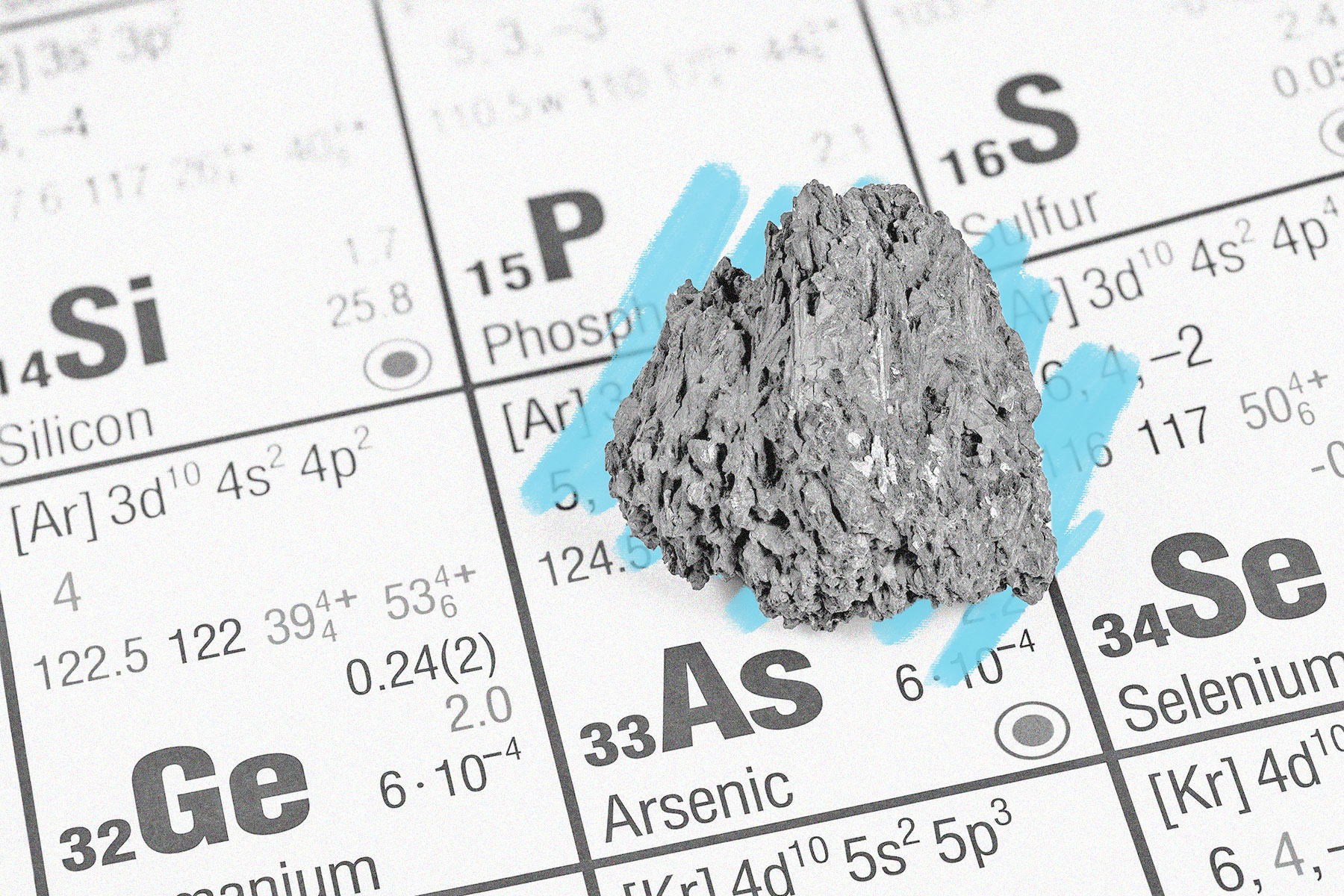

Why Victorian women ate arsenic (on purpose)

Tuesday, April 2, 2024

|

Victorian-era women ate arsenic as a beauty treatment. |

World History |

|

| |

| In 1851, a Swiss physician published a report in a medical journal about the "toxicophagi," a group of people in modern-day Austria who routinely consumed arsenic; they knew it was poison, but thought they could develop an immunity to it by starting with small doses and gradually increasing the intake. The report's author claimed that arsenic gave them great energy, sparkling eyes, and wonderful complexions, but noted that after long-term use, unsurprisingly, "most arsenic eaters end with an inevitable infirmity of the body." | |

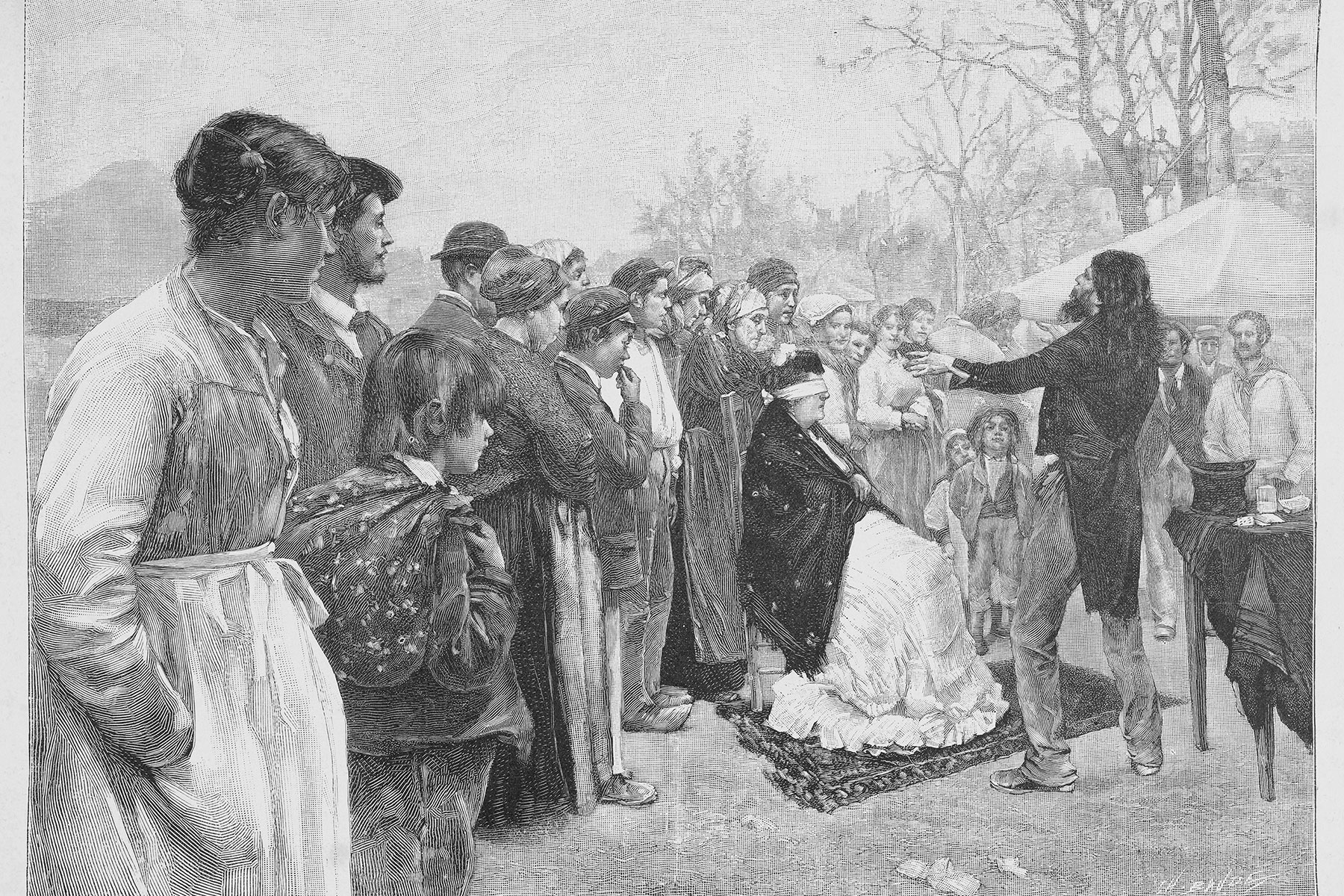

| After the article was published, beauty writers told stories of women in Bohemia (modern-day Czechia) who bathed in "arsenic springs" as skin care. It became a popular treatment for women chasing a naturally wan look — as opposed to the "painted ladies" of the day, who used heavy makeup to appear pale. Arsenic-based "complexion wafers" started hitting store shelves; Dr. James P. Campbell's Safe Arsenic Complexion Wafers promised relief from blemishes and "a deliciously clear complexion," and were sold well into the 20th century. These wafers reportedly had a very low dose of the toxin, but because there is no such thing as "safe" arsenic, the wafers were still fatal for some consumers. Legitimate doctors warned against their use, and at least one physician in San Francisco worried that arsenic poisoning was going undiagnosed because women neglected to tell their doctors they were taking it. | |

| |||

| |||

Not Your Grandpa's Hearing Device | |||

| Thank you for supporting our sponsors! They help us keep History Facts free. |

| |||||||||

By the Numbers | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

Victorian women also rubbed mercury on their skin as a beauty treatment. | |||||||||

| Arsenic wasn't the only dangerous beauty compound to have widespread usage in the 19th century; lead-based white makeup was popular among women in the Victorian era, and ammonia factored into many skin care routines. Another popular trend was using mercury on your skin. Vermillion, a red pigment that's a form of mercury, was used to tint lips and flush cheeks. A widely used skin cream that launched in the 1880s contained mercury until the 1930s. In the 1870s, a beauty writer with Harper's Bazaar even recommended rubbing a compound that included mercury on your eyelids to encourage eyelash growth. At the time, mercury was found in many everyday items, and scientists had only identified mercury poisoning as a risk a decade earlier. | |||||||||

| |||

Recommended Reading | |||

| |||

| | |||

| |||

| | |||

| + Load more | |||

| |||

| |||||||||

| Copyright © 2024 History Facts. All rights reserved. | |||||||||

| 700 N Colorado Blvd, #513, Denver, CO 80206 | |||||||||

posted by June Lesley at 4:00 AM

![]()

![]()

.png)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home